Abb. 1: Mama Gaou paints Savo Onivogi. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg, Nyanguézazou, 1987

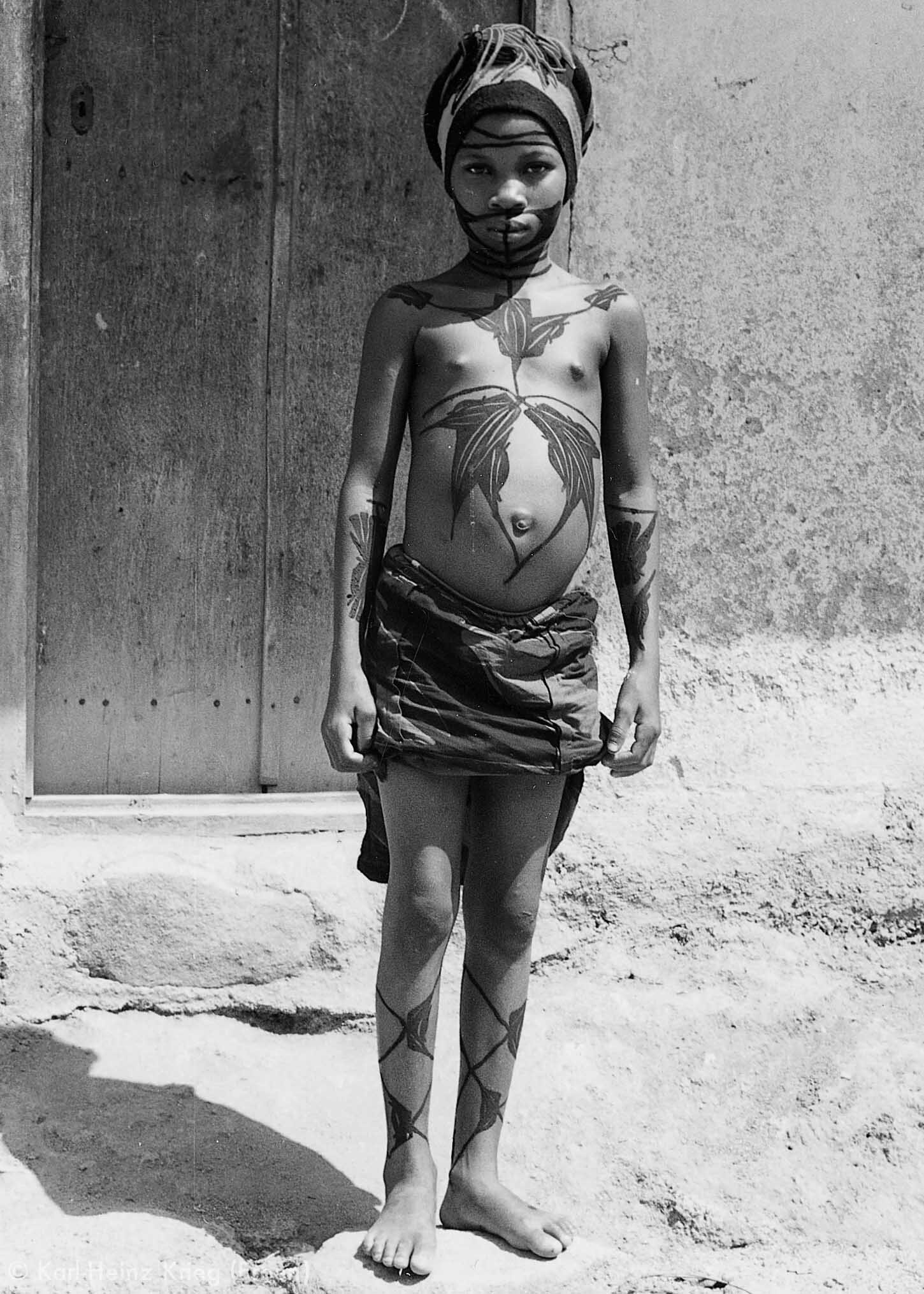

Abb. 2: Savo Onivogi with body painting. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg, 1987

1987 - First trip to the Loma Region

“After studying the tradition of batik printing in West Africa for years, I was on my way to Kindia in the Susu region (Guinea) in the spring of 1987. Several of the influential batik artists whose work I had studied in Ivory Coast were economic emigrants from "socialist" Guinea. They had learned their trade in the city of Kindia, and I wanted to add to my extensive collection of Ivory Coast printing blocks and continue my studies of the batik tradition on the spot.

The fact that we can present the work of the Loma painters today is due to a number of coincidences. Before leaving, I had read research and travel reports about Guinea from the Hamburger Völkerkundemuseum, since until then I hadn't known much about the country's population apart from the Susu and the names of the Loma or Toma. Unfortunately, I found mostly old travel reports, which couldn't help me much.

Actually, I would have wanted to drive to Kindia on a northern route via Mali, Siguiri, Kankan and Kissidougou, because in the rainforest area of southern Guinea the rainy season starts in full as early as April. Only because I made the trip with Alassan Fofana - who was a Malinke from Konebadou, a larger market town on the edge of the Loma area - we chose this rainforest route through the southern Ivory Coast, via the border town of Danane to Lola, Nzérékoré and Macenta, the district capital of the Loma.

In the Loma village of Passima, near Macenta, we arrived in the evening and asked the village elders for a place to sleep. We were entrusted to a family who sponsored us for the night. When I drove my car into the homestead, there was a woman, Komassa Guilavogi, who was painting the body of a little girl; I also saw abstract paintings on the walls of the surrounding buildings that I had never seen before in Africa. I was so excited that I almost forgot my destination and the reason for my trip, the batik printing. Fortunately, in order to print batik stamps, I had taken enough black batik ink and typewriter paper with me. So I was able to ask my hostess the next morning to paint some samples of her house and body paintings. I made a base for the sheets of paper from an old cardboard box, and she had no difficulty in transferring her patterns onto the paper. Komassa Guilavogi had also created the paintings on the inside and outside walls of the neighboring houses, and so she clearly had experience with flat surfaces.

We then drove on through the Loma region along the southern border with Liberia. I noticed the paintings on the houses in some villages, e.g. in Bauléma. It became clear to me that the works in Passima were not an individual idea of a single person, but that they had to be evidence of an ancient tradition. There had to be much more to this work. I was able to judge that very soon: these paintings with their clear lines were very consistent and of a mature strength, of an abstraction that impressed me. So I decided to stay in the area for a few days. It was again by chance that I took the narrow path that led to the village of Nyanguézazou. The residents were very astonished that we had dared the arduous ascent to their mountain village. It would have been much easier to find a place to sleep in the villages directly on the main road. They looked for a parking space for us and a family who drew us the bath water from a spring below the mountain.

The next morning I wandered through the town, greeted the elders and saw very beautiful house paintings again. When I asked, I was taken to Gaou Béavogi (Mama Gaou), a respected dignitary in the area. At the initiation of women in the year before she had painted the meeting house for the girls and the houses for the male dignitaries. She herself, as well as some of her friends, were willing to paint some traditional patterns on paper for me. This required preparation; and so we stayed a few days. Early in the morning Mama Gaou would collect leaf panicles, then she would mix the traditional earth colors of rust and ocher; she used black as the organic color. Only this black paint, made from charcoal and the oil of the Podai tree, is applied to the body. This tree, which supplies the color-binding oil, also gave the actual process of body painting its name: Podai. I built a little table again, and Mama Gaou applied the color to my typewriter paper with the panicles. However, the greasy black color smeared the paper - a disappointment. The results were better with the black batik paint I had brought with me. The earth colors, which only appear on house walls, partially peeled off after drying. However, I was able to bring some drawings, safely packed, to Germany.

The climax of our stay was when Mama Gaou suggested painting a young girl who was visiting her from Macenta. Her name was Savo Onivogi. Mama Gaou spent a whole day painting the girl's body. This is how the photo documentation of the painting of this girl came about. From the fascination of this experience, the Podai painting project was born (Fig. 1 and 2).

In 1989, 1990 and 1991 I made three more trips to the Loma region. I had been encouraged to do so in Germany by many friends to whom I had shown some sheets. I prepared these trips thoroughly and sought advice from artist friends on how to buy the right paints and other materials. Now the women could use emulsion paints - in their traditional shades of rust, ocher and black - to paint on paper, cardboard and plywood panels. The attempt to have the women paint with fine marten hair brushes failed: they continued drawing with the leaf panicles they had collected themselves.”

Abb. 3: Dancing girl. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg

Abb. 4: Dance of the Angbai mask. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg, Segbémé (Guinea), 1989

1989 - Initiation celebration for the girls and women from Segbémé

“When we were on our way to see Mama Gaou in Nyanguézazou in 1989, we were refused an overnight stay in a Loma village. In retrospect, this unusual behavior turned out to be another lucky coincidence. We were forced to continue our travel on the same day. When we arrived in Nyanguézazou in the evening, we were informed that Mama Gaou would be leaving the next morning in order to help with the women's initiation in Segbémé for a week; so we would have missed her. That night she sent a messenger and informed the elders of Segbémé that she was going to bring us to the celebration. Because of her high reputation, we were accepted as guests of Mama Gaou.

The next morning we drove to Segbémé together. When we left the main road at Bokpozou and wanted to drive on the widened footpath through a coffee plantation to Segbémé, we could not reach the mountain village with our car. Before the ascent to the mountain village there were only two thin logs over a small river, enough for a bike or moped. We abandoned the car and took our personal luggage with us, and I carried Mama Gaou's travel bundle on my head. In single file we climbed the steep path to the village, where we were enthusiastically received. The young men of the village quickly cut down a few small trees, laid them over the river and built a bridge for our car. The preparations for the celebration were in full swing. Many friends and relatives had come from far and wide to experience it. In the bush camp there were about 35 initiates, as well as all Podai painters and dignitaries of the women's association, in order to prepare for the big event, to paint the initiates and to adorn them with wonderful costumes.

And then the time had come: women's groups played music, the old women stood in formation, and the initiates came from their bush camp in a long procession up the mountain and marched into the village to the cheers of the guests. For four days we experienced dances, many games and plays that the girls had previously rehearsed in the bush camp: various girls danced through the village with a large hoop to playfully “catch” their future husband. Girls placed their “first baby” - a wooden doll (Domi) made in the bush camp - in the arms of a man who could only buy his way out with a gift of money. Girls imitated the dance of the Woniléghagi bird mask. This is a mask made by men, which women are also allowed to see. Finally, the Angbai mask appeared (Fig. 4), which had protected the girls for the entire duration of the bush camp. Now as a reward the Angbai mask was allowed to “fish” the most beautiful initiate with a long liana rod, to the amusement of the audience.

We met a lot of people during these festivities. All known Podai painters and dignitaries of the women's association from the area had come, Mama Gaou introduced us all. She told her friends why we came to see her, and they were ready to help us after the celebration. With the permission of the elders from Segbémé we were allowed to stay longer and were able to work with some Podai painters, including Kolouma Sovogi.

With the full support of the Council of Elders, the village of Segbémé had become the new Podai center, which meant an enormous improvement in the value of the village compared to neighboring villages. Today it is clear to me that through Mama Gaou's spontaneous invitation to the initiation festival in Segbémé, I “fell into a jungle river whose flow and depth I did not know”. In 1990 and 1991 further research trips followed to Segbémé, where I worked with the Podai painters and was able to deepen my knowledge. I had to learn that you can plan trips like this at your desk, but things can happen in Africa that you cannot imagine at home.”

Abb. 5: Kolouma Sovogi paints the house of Karl-Heinz Krieg. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg, Segbémé, 1996

Abb. 6: House where Karl-Heinz Krieg lived. Photo: Karl-Heinz Krieg, Segbémé, 1996

1996 - the last trip to Segbémé

“My original intention was to end my Podai field research in 1991. From four research trips I had brought along 1,800 Podai paintings along with many interview texts and field photos. All of this had to be recorded and processed for a Podai exhibition in the Völkerkundemuseum Hamburg until 1995. However, during the preparations for this exhibition, I noticed that we had too few large-format works for exhibition projects in museums. It was difficult to exhibit the pictures of some artists in larger rooms because their work, to put it a little exaggerated, was only "stamp size". I noticed myself that something was missing in this collection, but for a long time I couldn't get used to the idea to travel to Guinea again to continue to work with the Podai painters. Although I was a little tired, some friends, artists and museum people finally convinced me to do the task again, because in their opinion it was most important for the Podai cause.

My friends asked themselves how the Podai painters would behave if, for example, they were given a wide range of acrylic paints and encouraged to work completely freely. In their opinion, much had been copied of body painting and it would perhaps be a great liberation for the artists and thereby create a new generation of works painted in the Podai style. The best painters should paint large canvases. Another artist came up with the idea that I should try to model a girl's body with plaster bandages and then have the models painted by the best podai artist. I was finally convinced of the need for another field trip to Segbémé. With so many exciting questions I became very curious and tried to imagine how the painters would deal with these new possibilities.

All these good ideas and dreams were one thing - the planning and successful implementation of such a project was another matter. Almost four years had passed since my last trip in 1991. In all that time I had few contacts with my friends in Segbémé, not even with the artists, because they had no postal addresses in their villages. In the meantime, terrible civil wars had broken out in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and many residents had to flee to the hinterland of Guinea. The Loma region in particular lies along the Liberian border, and many refugees have sought refuge in the area around Macenta, our work area. Didn't it seem life-threatening to travel to these areas? I couldn't find a quick answer to this question.

Fortunately, my friend Alassan Fofana worked in Accra, Ghana. I discussed with him in Accra the question of another trip to Guinea, and then I gave him the reasons why I wanted to tackle this project again with him. I cannot make such far-reaching decisions on my own, and in the end I know very well that the success of a trip depends on the technical preparations, but also especially on experienced, loyal partners. Alassan was on fire. I sent him on a two-month discovery tour. After his trip, Alassan returned to Accra, and we met afterwards in Lomé, Togo, where he brought me a reply from the village chief of Segbémé and letters from important Podai painters. They were all ready to work with us. Since my partner saw a research trip in the spring of 1996 as possible, we made plans. I returned to Germany to start the technical preparations here.

Never before had I prepared a trip to Guinea so thoroughly: artist friends showed me how to prime a canvas; my family doctor put on a plaster bandage and showed me how I could use it to model a body, another artist friend gave me a painted face mask that he had made from plaster bandages in art class with his students. I calculated the amount of acrylic paints, primer, painting pads and cardboard in various sizes and bought all the material here. In Guinea in the rainforest, this is not a common commodity! I then packed everything in my off-road vehicle, stowed it in a container for safety and because of the risk of theft, and shipped it to Lomé, Togo. Alassan and I were already in the port in Lomé when the ship with our container arrived. Nothing had been stolen from the locked container, and we brought the car safely out of the port area with all the valuable materials. Without a long stop we drove off and chose the northern route via Burkina Faso, Mali, via the border crossing at Siguiri to Guinea, Kankan, Kissidougou directly to Segbémé, in the region of Bofossou.

The welcome in Segbémé was warm as always. Only the village chief did not feel comfortable because he could not repay my old loan and he had also used the money for my round house, which should have been built before my arrival, for other "short-term" purposes. The reason was very simple: The traditional round house was not built because the elders could not imagine that a white man would want to live in such an "old-fashioned" round house with a grass roof - since everybody wanted a square house made of cement stones and a corrugated iron roof. After two weeks my house was ready. It was a double-paid community effort by the village, the women brought in the water, tamped the clay floor and limed the house with crisp white kaolin. Kolouma had meanwhile arrived and she was very proud that she was allowed to paint my house (figs. 5 and 6).

At the previous working meetings in Segbémé, I had learned to involve the old dignitaries in all important decisions and to consult with them. Paying the painters and all those who worked with us was a very sensitive issue. The success of our project was only guaranteed if I didn't make any mistakes. And so I came up with the idea of negotiating the wages of the women with the elders and the village chief. No payment was made behind the back of the elders: they took the wages for all women into their hands, they checked the calculation and then passed the full amount on to the respective women. Since these artists had never been paid for their painting work before, but traditionally this is regulated among each other with gifts, we had to find a workable basis. I asked the elders and the painters about the daily rates a farm or contract worker was entitled to. After I knew these daily rates, I knew what I had to do: I offered all women the same payment: for a day of painting they received three daily rates for a farm worker, plus food, a place to sleep and a fare. Because of the early rainy season, we repeatedly had the problem of calling the women to Segbémé to paint in the middle of the farming season. The high pay for local conditions made it possible for the women farmers to employ two or three field workers for themselves. One of the women was very honest with me and smiled: "This is good business for me because without work (painting is not work) I can pay three young men who do all the heavy field work for me."

The women weren't paid per painting, so they weren't under any pressure to perform. I told them to take a lot of time and do everything in a playful way. I didn't care whether a woman painted two or five works a day: the quality of the paintings was the only measure of whether she was allowed to continue working. At the end of their work, they got their pay in front of the council of elders. As a gift, each woman received fabric for a beautiful dress and a bonus, the amount of which I decided and which I explained to the elders and the painters. The women were all highly motivated. One had the feeling that a kind of competition was taking place between them: each woman defended not only her professional honor and her name, but also the honor of her village.

It was not easy to find a workable solution for priming and painting large cloths: it was impossible to work outdoors because of the enormous insect plague. The insects were magically attracted by the bright white surface and they had developed the bad habit of dropping their "kaka" on the primed cloths (as the Loma say).

In the village I was able to rent a half-finished modern building with a fixed roof and a large reception hall. Now I went to Macenta and had a carpenter build three wooden stands for me, on which I put thick wooden boards. The result was a work surface of 1.50 x 2m, on which the canvases were fixed with nails. Most artists adapted quickly to the large-format work, as they were already used to painting large house walls. The only change was that the cloth wasn't pinned to a wall like I tried first, but that I stretched it flat on the work table. Because they were painting from each side, the artists had to walk around the work table. This required full concentration so that the paint did not drip onto the cloth. It took a woman about a day to paint a large cloth; although no woman sketched out her pattern, but developed the picture freely, from the center, I did not have to paint over a single one of the 18 cloths.

During our six weeks in Segbémé, the political situation deteriorated noticeably. Because bandits from Liberia crossed the border at night, I even had to hide my car. In the farming villages, in the region around Macenta and Bofossou, Loma refugees from Liberia sought refuge and upset the social fabric. Women had lost their husbands in the civil war and fled across the border with their young children. It bordered on a miracle that we were able to complete our work successfully despite all the hardship. In the following two years, the areas around Macenta, Bofossou and Guékedou were badly affected by the effects of the civil war in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and many people had to flee.

Our trip in 1996 was perhaps one of the last opportunities to complete the study of Podai painting. How great the success and how good the mood was is also expressed in the number of works painted on this trip: 18 women worked with us for six weeks and painted a total of 1,800 pictures (which is exactly the same number as in the four previous trips together).”

Text: Karl-Heinz Krieg, 2003

Aus: Podai - Malerei aus Westafrika, museum kunst palast, Düsseldorf, 2003